The Coffee Shop

Sigfried Heller, or Sig (pronounced with a zed) was sitting in a coffee shop totally dejected after being turned down by yet another Silicon Valley Venture Capital fund. He and his childhood friend, Zachary Montserat, were trying to get a decent WiFi connection but nothing seemed to be working.

“I’m gonna try the cell network” Sig says.

“Forget it” says his buddy Zach. “I tried that already. It’s worse.”

Then they saw it. Both of them at the same moment.

GREY MATTER SECURES $500M FUNDING FROM SILICON VALLEY VC. NASDAQ IPO HOTLY ANTICIPATED

“Seriously?” The lead investor is the firm we just got turned down by. They knew this was coming out the whole time they were quizzing us for the secrets related to our approach. Our tech. Assholes.

Guinness

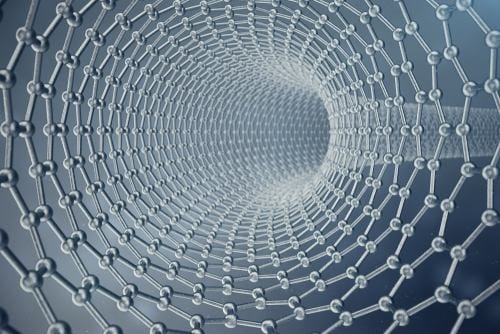

Sig and his rival, Grey Matter’s CEO Anil Amlani, both grew up in Vancouver. Canada. A video game, come tech hot spot in North America that had everything from mountains and ocean to exotic cars and yachts for the rich and privileged to play with. Both Sig and Anil each had plenty of access to resources more valuable than money when getting a startup off the ground. Network. That leads to the right introductions, influential board members and, of course, funding. With all the other elements in place early funding comes along. The trick is to keep that money flowing. The big ideas Sig and Anil had been developing were extremely advanced. They were working with Graphene, the early 20th Century super-material with a long list of properties from superconducting to storing both energy and information in vast quantities. Unlocking the power of Carbon, the most common element in our solar system, to both store energy, transport it with no loss, then dispense it when needed would completely change the world economy. And Anil had figured out how to use the same basic configuration applied in batteries, to store information. On the same devices. So batteries are also hard drives, and vice versa. Sig had his own version but Anil had something more: Funding.

The prize was immense, but it takes many years of attempts, iterations and failure before success ever shows up. If it does at all. And all of that costs millions of dollars. For both Sig and Anil some of that early money came from government grants or university funding programs intended to encourage early stage advanced materials science. But the real money needed to break through, the tens of millions, usually had to come from VC funds or other sources. Interestingly, Anil had a connection to a little-known trust fund looking to invest in just this sort of thing.

The Guinness family, owners of that famous stout served across the globe, also happened to own vast tracts of land on the slopes of the north shore mountains in Vancouver dating back over 100 years. They are still slowly being developed, over a now centuries-long plan that actually included the building of the iconic Lion’s Gate Bridge in 1934 to improve access. Prior to that it was only really reachable by ferry or after a fairly long drive. The locals called it the British Properties (the BPs for short). And it was that investment trust, that connection, Anil exploited and somehow convinced the stewards of that family fortune to fund his project. Their sprawling financial empire had all manner of investment funds, and one just happened to be looking for early stage companies to invest in.

They were the perfect backers. An endless tolerance to provide capital that never seemed to run out. Anil thought it was the perfect match too, but once the Silicon Valley VC fund started doing their Due Diligence as part of a huge investment, it quickly became apparent what the fund managers were doing. As it turned out, they were using the losses from Anil’s company, Grey Matter, to launder money made in other areas that were not of a legal nature. They would have been fine as long as Grey Matter continued to lose money. But once the company stumbled onto a breakthrough and attracted other investors, the whole thing unravelled. And Grey Matter was at the centre of it all. No one knew if the management of the company was complicit with the scheme or had been duped. Or even if their patents were just a bunch of other lies. Few cared enough to spend the additional money required to get a truthful answer.

Under Anil, Grey Matter had poured funding into an elaborate patent portfolio protecting every conceivable application of the breakthrough science they had been developing. Sadly, all those patents meant nothing when the company suddenly had to make payroll the next month and otherwise had no revenue, no new funding and apparently no help coming anytime soon. Enter the modern invention of Debtor In Possession financing.

What The Hell Does DIP Mean?

Zach came busting into the room, stumbling over both his discovery and his immediate need to share it with Sig.

“I’ve figured it out” he says. “If we can convince one of these debt funds to give Grey Matter DIP financing we can secure that loan against their patents for a fraction of what they’re worth. Less than what it actually cost to file the applications, if we’re lucky.”

Sig was all ears. “Tell me” he blurts out.

Zach understood finance. But not, how to balance your checkbook, pay off your credit card and budget to save a little every month, kind of finance. He knew how giant hedge funds invested their capital, bought companies and then sold them a few years later for multiples of the capital they originally invested. He told Sig that to avoid filing for bankruptcy, Grey Matter would need a small amount of interim capital (cash) to pay employees, lawyers and keep the business going while they sorted out where their next funding would come from or who would buy the company. The money was clearly not going to come from the stock market, that ship had sailed. Once the lead investment bank dropped the IPO over a “Due Diligence issue” no one would touch them. Their $500 million in VC money was also gone. A prominent Silicon Valley VC could not have criminal controversy like this associated with them so they were talking to their own lawyers before the second tranche of funding was released. Grey Matter had ramped up expenditures in anticipation of their IPO, not to mention the remaining tranches of VC money. Now, they were out of cash and desperately needed an infusion to make payroll. Zach’s plan was to get a debt fund to offer Grey Matter DIP financing. This sort of debt goes in when a company is about to declare bankruptcy, or has already done so, and because it is being provided with full knowledge the company is potentially broke, it gets paid back first. “The trick” Zach says “is making sure it doesn’t get paid back.” Sig gives him a quizzical look but waits for the answer, knowing it will come. “When the company cannot pay the loan back the lenders start selling assets to clear liabilities. And we get them to sell the patent portfolio to us.” Zach looked very pleased with himself. “In fact, we negotiate for specific patents to be designated security against the DIP loan from the start.”

“How much money do we need to get a debt fund to lend them?” asks Sig.

“About $20 million” responds Zach, without missing a beat. “And I already struck a deal with an equity fund to put up the $30 million to buy the patents from the Debt fund. When the debt fund gets the patents, we will pay them $25 million for the Graphene patents. $30 million for the whole portfolio. They will be under a Non-Disclosure Agreement so they can’t speak to anyone else to sell the assets. We become the only buyer for the patents and the other creditors scrap over the remaining assets.” Zach had truly thought this through knowing the other creditors will want to jettison the assets that cost the most to maintain; the patents. And if they eliminate the DIP financing at the same time, so much the better. “The best part” Zach continues “ is that a $5 million return on a $20 million DIP loan in a few months is the greatest return that debt fund will ever see. At $30 million, the fund’s partners will all be buying new summer places.”

Sig knew the value of those patents was greatest in his hands where they would simply protect the advances he had already made in his own company. But where the hell had Zach found $30 million when they had been pounding the street to raise an amount less than that for months but had nothing to show for it? “Oh no, not the same VC that just shut us down? I thought they couldn’t be anywhere near this mess?”

“They can’t,” replied Zach. “But once we strip out the patents, it no longer involves Grey Matter and they will invest in us. At a much lower cost base as well. They’re all over it.”

To most people this kind of chicanery would seem immoral. But in the world of Venture Capitalists, it gains them respect. If it works. The VC that turned them down obviously understood the value of the patents, but they needed a company to exploit them. The patents themselves weren’t valuable until they were protecting a commercial technology. Sig’s company WAS that commercial technology, and they had all the right people in place to make it a reality. Once Zach lined up the debt fund and had them provide the $20 million the VC fund was on them “like a fat kid on a Smartie” Zach chortles. The greed involved surprised even Sig, and it brought the plan together with alarming speed.

As Sig thought about it he realized it was pure genius. The debt fund would be doing whatever they could to ensure Zach and Sig got the full patent portfolio solidifying their $30 million return on investment. And the VC would get the same crack at this Graphene battery and information storage technology at a much lower cost. For it to work, however, it all had to come together inside just weeks of negotiating and document drafting, most of which was done in a designated boardroom at the Silicon Valley VC’s plush offices overlooking San Francisco Bay. At one moment, as they were hunkered down in the boardroom surrounded by laptops, lawyers and finance types, someone asked what the patents were actually worth. One of the smart-ass finance geeks crunching numbers in the corner blurts out “$300 million. Minimum.”

Immediately, another voice is heard across the room, booming “Those patents are NOT worth $300 million dollars.” The room goes silent for a moment as this team of people burning through hours over weekends with no real breaks begins to process that information. What the hell are we doing all this for if those patents aren’t worth some huge amount more than they were paying? Then it comes. The voice continues “A single application of one patent is worth many times $300 million, so anyone who says they are only worth $300 million should get the hell out of here right now.” It was Sig. The most authoritative declaration anyone in the room had ever heard, and no one questioned it.

Fin